노벨문학상 수상 축하합니다! '내이름은 빨강' 느무느무 좋게 읽었던지라, 파묵의 수상이 기쁘다.

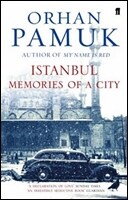

파묵의 책 중에서, 유독 읽고 싶은 것이 있다. '이스탄불' 이라는 작품인데 작년에 나왔으니 신간이라면 신간이다. 아직 국내 번역 안 됐고 영어로 된 걸 살까 하다가 말았는데... 노벨상 탔으니까 이제 곧 번역돼 나오겠지? 이 작가가 이스탄불을 어떻게 그렸는지 궁금해 죽겠당...

Turkish Writer Wins Nobel in Literature By SARAH LYALL / New York Times Published: October 12, 2006 LONDON, Oct. 12 ? The Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk, whose exquisitely constructed, wistful prose explores the agonized dance between Muslims and the west and between past and present, won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature today. Announcing the award from Stockholm, the Swedish Academy said in a statement that Mr. Pamuk’s “quest for the melancholic soul of his native city” had led him to discover “new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures.” Mr. Pamuk, 54, is Turkey’s best-known and best-selling novelist but also an increasingly divisive figure in a nation pulled in many directions at once. A champion of freedom of speech at a time when insulting “Turkishness” is a criminal offense, he has run afoul of Islamists who resent his Western secularism, and Turkish nationalists who object to his unflinching, sometimes unflattering portrayal of their country. The Swedish Academy never offers nonliterary reasons for its choices and presents itself as being uninfluenced by politics. But last year’s winner, the British playwright Harold Pinter, is a prominent critic of the British and American governments, and there were political implications once again in the choice of Mr. Pamuk. “You’re beginning to notice a certain sensitivity to trends ? they are giving the prize as a symbolic statement for one thing or another,” Arne Ruth, former editor-in-chief of the Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter, said in an interview. Of Mr. Pamuk, he said: “he is a symbol of the relationship between Europe and Turkey, and they couldn’t have overlooked this when they made their choice.” Mr. Pamuk, who said in 2004 that he has begun “to get involved in a sort of political war against the Turkish state and the establishment,” is currently spending a semester teaching at Columbia University in New York. Nationalist Turks have not forgiven him for describing the Turkish campaign against the Armenians during the First World War as genocide ? a matter of bitter contention ? and last year he narrowly escaped prosecution when a group of nationalists began a criminal case against him for remarks they considered anti-Turkish. Because of the deeply mixed feelings Mr. Pamuk inspires back home, some prominent Turks had to walk a fine line today, expressing pride while trying to play down the significance of his political views. “I want to believe that the Nobel Prize was given to him purely on his literary talents, but not political declarations,” Egemen Bagis, a member of Parliament from the ruling Justice and Development party, said. At the same time, Mr. Bagis said that the prize “shows how far Turkey has come in its contribution to the world’s arts and literature.” In a brief interview with the Swedish newspaper Svenska Daglabet, Mr. Pamuk said today that he was “very happy and honored” and trying “to recover from the shock.” Born to a wealthy, secular family of industrialists in Istanbul in 195, Mr. Pamuk originally meant to be an architect. But he defied family pressures, quit architecture school and became instead a full-time writer, publishing his first novel, “Cevdet Bey and Sons,” about three generations of a family, in 1982. Among his best known works is “My Name is Red.” The novel, first published in Turkey in 1998 and subsequently translated into 24 languages, introduced Mr. Pamuk to a wider audience and cemented his international reputation. Set over nine winter days in 16th-century Istanbul, it is at once a mystery, an intellectual puzzle and a romance with a range of narrators, including a murder victim who opens the novel by saying, “I am nothing but a corpse now, a body at the bottom of a well.” In 2003, it won the $127,000 IMPAC Dublin literary prize. “Nothing changed in my life since I work all the time,” Mr. Pamuk said at the time. “I’ve spent 30 years writing fiction. For the first 10 years, I worried about money and no one asked me how much money I made. The second decade I spent money and no one was asking me about that. And I’ve spent the last 10 years with everyone expecting to hear how I spend the money, which I will not do.” “Snow,” published in the United States in 2004, expands further on themes ? alienation, religion, modernization, the hidden corners of Turkey ? that Mr. Pamuk has explored over and over in his work. Writing in the New York Times Book Review, Margaret Atwood called the novel “not only an engrossing feat of tale-spinning, but essential reading for our times.” The Turkish public reads Mr. Pamuk’s work, she said, “as if taking its own pulse.” Ms. Atwood continued: “The twists of fate, the plots that double back on themselves, the trickiness, the mysteries that recede as they’re approached, the bleak cities, the night prowling, the sense of identity lost, the protagonist in exile ? these are vintage Pamuk, but they’re also part of the modern literary landscape.” Mr. Pamuk was quick to denounce the fatwa against Salman Rushdie over Mr. Rushdie’s work “The Satanic Verses.” In 1998, he turned down the title of state artist in Turkey, saying, “I don’t know why they tried to give me the prize.” Mr. Pamuk’s Nobel comes at a particularly tricky moment for Turkey, whose efforts to join the European Union are viewed with suspicion by its own nationalists, by Europeans who worry about the country’s high proportion of Islamists, and by European governments, who are insisting that it first adhere to Western standards in human rights and justice. Coincidentally today, a bill that would make it a crime to deny that the Turkish killing of Armenians from 1915 to 1917 constituted genocide was passed in the lower house of the French Parliament. And from Armenia, the foreign minister, Vartan Oskanian, praised what he said were Mr. Pamuk’s courageous words about the past, in a statement that is bound to irritate Turkey. “Orhan Pamuk ventured into issues of memory and identity, and with intellectual courage and honesty, explored his own history, and therefore ours,” Mr. Oskanian said in an e-mail message to The New York Times. “We welcome this decision and only wish that this kind of intellectual sincerity and candor will lead the way to acknowledging and transcending this painful, difficult period of our peoples’ and our countries’ history.” Reporting was contributed by Ivar Ekman from Stockholm, C.J. Chivers from Moscow, Nina Bernstein from New York and Sebnem Arsu from Istanbul.

|

| 아, 나도 이 뉴스보고 왠지 좀 반갑던데(왜 그런거지?-_-) 언니, 다음 주 즈음에 한 번 갈께요, 아지 님 책 갖고.... |

| 그치? 나도 반갑더라고. 내가 왜 이렇게 기뻐하는지는 나도 잘 모르겠지만. ^^ |

| 나도 반갑네. 히히. 왠지 아는 사람 같은 느낌이랄까. ^^;;; |

| 나도 웬지 반가웠는데 ^^ |

| 와와 우리 모두 반가웠던 거야 ^o^ |

| 나도 왠지 즐겁더라니. 생기기도 잘생기셨구만.. |

| 뭐 책을 읽어봤어야 반가울텐데.-_- ㅋㅋ |

| 그 책 맞아요, 여러가지 다른 표지들이 있더라고요. |

'딸기네 책방' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 20세기 동남아시아의 역사- 간만에 재미난 책 (0) | 2006.10.19 |

|---|---|

| 만델라 자서전 - 자유를 향한 머나먼 길 (0) | 2006.10.16 |

| 칭기스칸, 잠든 유럽을 깨우다- 칭기스칸 시대와의 낯선 대면 (0) | 2006.10.10 |

| 발칸의 역사- 언제나 어려운 이름, 발칸. (0) | 2006.10.07 |

| 남아프리카 공화국- 포장은 괜찮은 책 (0) | 2006.09.15 |